As high school and college athletes prepare for the fall semester of sports, experts are doing what they can to keep them safe after a July of above-average heat, and the next few months are forecast to be the same.

“The humidity is wicked high, and the heat index is even higher,” said Dr. Jason Zaremski, a sports medicine physician at the University of Florida.

Acting as the supervisor physician for the East Side and Bradford high school football teams in Gainesville, Zaremski sees football players as a susceptible group to heat illnesses like exhaustion and heat stroke.

He says the players are strongly encouraged to acclimate themselves, or condition, in the June and July heat before August training begins. If they don’t, they could face heat exhaustion or even heat stroke. It’s why he encourages coaches to acclimate players to the heat before training gets too intense; otherwise, they could begin to dehydrate and overheat.

“If your body gets that level, your internal temperature rises above 104 degrees, that's when something can become very severe, and you can go from having exertional illness to exertional heat stroke, and that could be life-threatening in some instances,” he said.

Since 1995, an average of three athletes (mostly high school football players) have died annually due to heat stroke, according to the American College of Sports Medicine. That average has remained steady despite education and preventative efforts, the ACSM said.

To keep players safe, Zaremski said that high schools are encouraged to follow the Florida High School State Athletic Association’s acclimatization schedule, which involves easing the players into intense practice.

For the first week, only single-practice days and players do not wear pads for the first three days. After about four or five days, it’s helmet and shoulder pads only. Two-a-day practices begin the second week.

“You're basically building the body up,” Zaremski said.

Central Florida’s heat by the numbers

The summer has been brutal for not just athletes, but also those who haven’t taken such precautions to manage the heat. Orange, Seminole, Marion, and Volusia all saw an increase in the number of heat exposure calls in June and July compared to last year. Orange and Volusia counties led the pack in the number of calls – Orange with 164, and Volusia with 143.

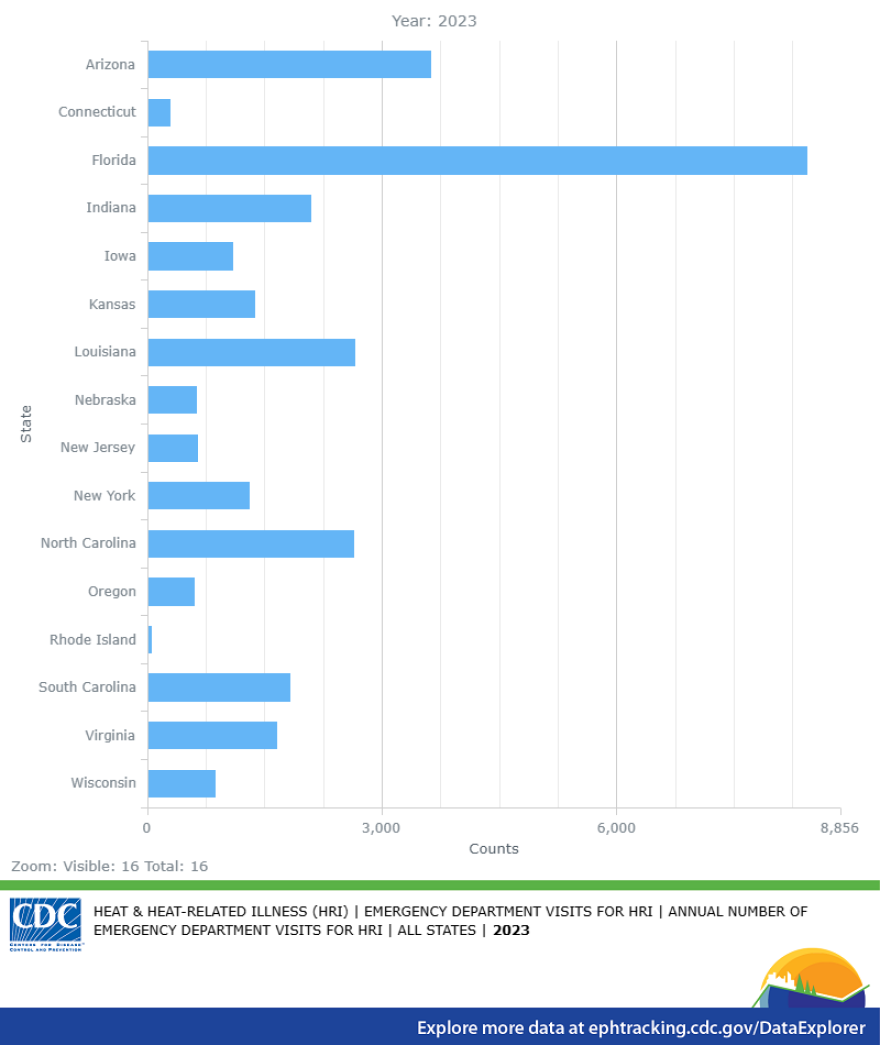

The state as a whole has also been experiencing more emergency department visits due to heat exposure, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2005, the rate per 100,000 people to be admitted to the ER was 3.5. Twenty years later, it’s 7.6. In the most recently available data, 2023, Florida ranked No. 1 with the highest total number of patients entering the ER for heat-related illness, with over 8,000 visits.

In Central Florida, both June and July tracked above-average in temperature, with average highs of 91.7 (June) and 92.8 (July.)

There were 14 heat advisories issued so far this summer, said Brendan Schaper, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Melbourne. It’s the third-highest amount since 2020.

Leesburg experienced a record-breaking heat in July with temperatures reaching 100 degrees, two days in a row, Schaper said.

Prepping for game day

The University of Central Florida Knights kick off next week at home. The NWS has predicted the week to also exhibit high temperatures, as part of a streak through October.

Central Florida Public Media reached out to the UCF athletics team about how it keeps players safe. They were unavailable for an interview, preparing for the season, but they issued a statement:

“The health and safety of our student-athletes is always our top priority at UCF. During summer workouts and practices in the Florida heat, we follow strict protocols that are based on medical expertise and best practices. Our training staff closely monitors heat and humidity levels, adjusts practice schedules when necessary, and builds in mandatory water breaks and cooling periods. Every workout is supervised by our certified athletic trainers, and our coaches and staff are trained to recognize signs of heat illness. Ultimately, we want our athletes to compete at the highest level, but their well-being will always come first.”

On the high school level, Zaremski said that players are told to wear loose and lightly colored clothing. They’re given frequent water breaks and told to rest in the shade, making sure everybody is ready for the big game.

“When you get out there and start sweating with the pads on and figuring a collision, contact and collision-based sport like football, it is something that should not be taken lightly,” he said.