It’s been one month since Florida banned fluoride in its drinking water.

Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill earlier this summer that outlawed water facilities from adding water quality additives such as fluoride.

Coincidentally, the day before Florida’s ban went into effect, Calgary, in Alberta, Canada, reintroduced fluoride to its water after stopping the practice 14 years prior. One of the big reasons why Calgarians voted to once again add fluoride to water was an eight-year study showing significant increases in tooth decay in second-grade children.

What happened in Calgary?

In 2011, city council members voted to remove fluoride from Calgary's water system, citing costs. Leaders said improving the system would be too expensive.

“How do you put cost on people's health in a budgetary item?” said Dr. Bruce Yahlonitsky, a dentist in Calgary. “Then we see the deleterious effect of what's happened.”

The practice of fluoridating water began after an experimental trial in the 40s in Grand Rapids, Michigan, showed favorable results in children fighting tooth decay.

According to Yahlonitsky, two years after fluoridation ended in Calgary, he started noticing more rampant tooth decay in young patients.

“We were seeing kids who had never been exposed to any fluoride in the water,” he said. “

And when you've got kids that are even under two years of age, who have all their teeth with decay on them, you have to take them into a hospital situation to treat them. They can’t be treated properly in a dental office.”

But was ending water fluoridation the reason?

The Study

Before the 2011 council vote, Lindsay McLaren didn’t know much about fluoride or dentistry.

“I really knew nothing about teeth. I didn't even know how many teeth we had,” she said.

McLaren is a community health researcher at the University of Calgary. She began looking into the research on fluoride and was disappointed to find that there wasn’t more new information.

“I was a little bit surprised it wasn't as strong as it's often felt to be by those in the public health community,” she said.

McLaren realized there was a golden opportunity for research. She decided to conduct her own study, which was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

She, along with a teamcompared second-grade kids from both Calgary and Edmonton, the other big city in Alberta, where fluoridation had been in place since 1967.

Over nearly eight years, McLaren and the team compared the dental hygiene of second-grade children from both cities, and then compared those results against historical data sets from 2004-2005 as well as 2009-2010. They also sent questionnaires home to parents asking about diets and dental hygiene routines.

Lastly, they also collected a small sub-sample of fingernail clippings as a fluoride intake biomarker. The fingernails were used almost like the dipstick in a car, checking the oil level.

“This is quite important, because fluoride intake, based on the fingernail clippings, must be lower in Calgary than it is in Edmonton. And if it's not, then something really significant has happened to offset the lack of fluoride in the water in Calgary, right?” she said.

And after 8 years, what McLaren and her team found was that cavities occurred more in the sample of kids from Calgary.

While about 55% of kids studied in Edmonton had tooth decay, in Calgary, that number was around 65%. Historically, children from both cities had around the same percentage of tooth decay issues.

“It's a statistically significant difference, so it's not likely to be due to chance,” she said.

The study highlighted another issue. Simply fluoridating water isn’t enough. Kids in Edmonton, where the practice has been in play, still had high levels of tooth decay.

“This makes it very clear that fluoridation is clearly not the only thing that's important here, but it's still important,” McLaren said.

Income inequality is high in Alberta, according to McLaren’s study, and significant social inequities in a child's ability to access dental care exist, exacerbating the issue. In other words, no longer adding fluoride to water could lead to a rise in tooth decay, depending on the setting, McLaren said.

In 2021, the question of whether to begin fluoridating water in Calgary was put to a vote. Sixty-two percent of those who voted said yes. It would take another four years to put the infrastructure back in place.

Will Florida be like Calgary?

McLaren says the jury is out. “You may not need fluoridation because you're providing the conditions for people to be well otherwise,” McLaren said. “To the extent that describes Florida, maybe it'll be fine, but I'm not sure that describes Florida.”

That’s something that concerns University of Florida researcher Dr. Olga Ensz. Her work focuses on dental deserts in Florida.

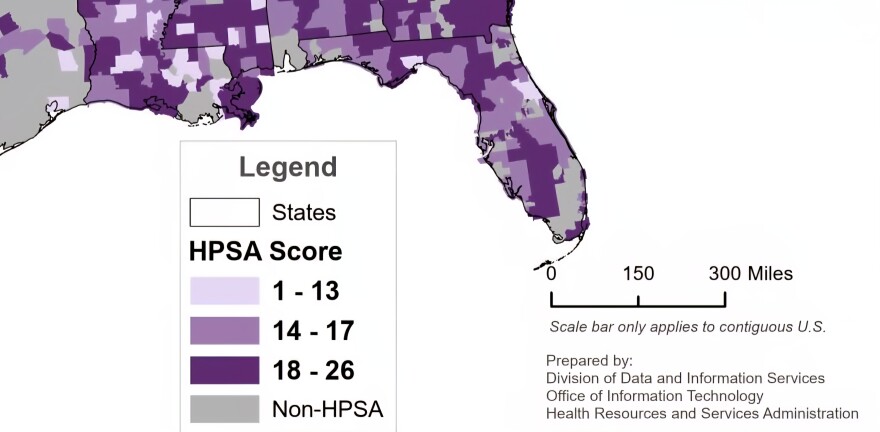

“Sixty-five out of our 67 counties are considered dental health professional shortage areas, which means there are not enough dentists to serve the population in those communities,” Ensz said.

Florida dental records by the numbers

Florida ranks 45th in the country for dental care, with 5.9 million people residing in a dental desert, according to KFF.

The Health Resources and Services Administration also found that Florida has 274 designated areas facing dental shortages, or communities that don’t have enough dentists for the population. According to the HRSA, that’s about 5,000 people for every one dentist. Central Florida makes up 20% of the dental shortage.

Data available from the Florida Department of Health also shines a light on the state’s dental issues, with nearly one in three Florida third-graders having untreated tooth decay during the 2021–2022 school year. It’s almost double the national average of 17% of children ages 6-9, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And in 2020, Florida had the highest rate of non-traumatic dental condition emergency department visits for those 14 years old and younger compared to all other states, according to the CareQuest Institute for Oral Health HCUP dashboard.

Historically, ER visits for dental have gone down in Florida, but between 2021-2023, every county in Central Florida saw increasing visits to the ER for dental conditions for ages 5 and older, FDOH records show. Marion and Volusia showed the greatest rates of increase.

Is fluoridated water the answer?

One of the reasons why children are the focus of fluoridated water studies is because of their exposure to sugary foods and the vulnerability of young teeth, said Dr. Ensz.

“They have less enamel on the outside, and so they're a lot more prone to getting cavities,” Ensz said. “Especially when dental hygiene might be poor, and when they do have challenges with accessing dental care.”

However, she’s not convinced community water fluoridation is the only way to address tooth decay.

Ensz said reducing the consumption of sugary foods would go a long way in addition to proper brushing and flossing, and seeing a dentist even if only once a year.

As for those without immediate access, Ensz said the state would need to invest in dental health programs, similarly to countries that don’t fluoridate water, like Japan, that practice fluoride-mouth rinsing with pre-school kids.

Several Florida counties do have school-based dental sealant programs, which are an inexpensive treatment where a dental provider will apply topical fluoride varnish, Ensz said. She’s hoping that in light of the fluoride cessation, the state will make up for it by investing in similar school-based programs.

“This is something that will require a lot of support,” she said. “This will be a challenge until we can really demonstrate through our policies, through our insurance, that oral health is part of overall health. And I think how our system is right now, it's unfortunately putting dental health in a silo, and that will lead to these issues, I think, to continue.”

How Florida became the second state to end fluoridation.

The day after Florida’s fluoride ban officially went into effect, Orange County resident Justin Harvey held a glass of water in the air, surrounded by a group of people, all beaming with smiles.

It was a celebration for their hard work over the last several years, convincing local municipalities to remove fluoride from drinking water.

“Thank you so much for being a part of this journey,” he said at the Water Bar/ Refill Station on Orange Avenue. “This is a cheers to a healthier future, and on the count of three, let's just say fluoride-free.”

The crowd echoed his toast in the small Water Bar, which sells Alkaline water, which is higher PH than typical bottled or tap water, it can be naturally occurring and contains minerals like magnesium and calcium. Some research suggests that Alkaline water has multiple benefits, such as improving muscle and bone quality, but overall research is divided on those benefits.

As for the group, they were jubilant.

“This is a very gratifying day that we've been waiting for for a long time,” Harvey said.

Harvey and others like him became concerned about fluoridated water after learning about studies linking the mineral exposure to lower IQ and calling it a “forced medication.”

While fluoridated water has always been a hot topic, the subject received renewed attention last year when Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. spoke about ending fluoridation. Not long later, Florida Surgeon General Joseph Ladapo issued guidance on ending fluoridation, citing studies linking lower IQ with fluoride exposure.

That association was identified in the National Institutes of Health’s National Toxicology Program: a meta-analysis, or systematic review of existing epidemiological studies on fluoride exposure’s potential cognitive impacts on children. Most of the studies reviewed were from China, and none from the United States. Most were also deemed to be low-quality (52/74), meaning they had a high risk of bias. However, the rest were deemed high quality and low bias.

Last year, the meta-analysis was referenced by a federal judge who relied upon it in his ruling in favor of an anti-fluoridation coalition, which sued the Environmental Protection Agency back in 2017.

All of that built the momentum for Harvey and other fluoride-free friends to speak with city and county leaders, convincing them to end the practice.

That momentum swelled with the most recent Florida legislative session, which saw the creation of SB 700, and eventually its signing into law.

Calgary’s return to fluoride doesn’t concern Harvey, nor does McLaren’s study.

“Most of the developed world doesn't fluoridate its water, so a lot of people worry about what the consequences of this could be. Are teeth going to rot? But the majority of places that remove it, or have never had it, have no issue,” he said. “In my opinion, we take the medicine out, and there's no drawback.”

As for what’s next, Harvey is looking at other states.

Earlier this year, Utah became the first state to ban fluoride. There have been movements in other states, like Arkansas and Kentucky, to remove it, but the efforts failed. Earlier this month, Connecticut signed legislation to keep fluoride in its water.

“Our entire goal is to replicate this for other states, and let other states do what we did. So we want to see that that's what we want to push. And I'm just happy to see that other states are encouraged by this,” Harvey said.