As officials and conservationists work toward protecting key land in the Florida Wildlife Corridor throughout the state, Seminole County is on the precipice of strengthening its already-important conservation land. And that will come down to a public vote in November.

An example of how an informed public can help land stay in conservation is right in Seminole County: the rural boundary.

Along the east side of the county is a boundary that separates urbanized areas from the East Rural Area, encompassing nearly 75,000 acres.

While it was first envisioned in the 1970s and adopted in the county’s comprehensive plan in the 1980s, the rural boundary was strengthened more in 2004 when Seminole County voters approved a referendum to keep it protected. The voters’ involvement helped prevent future development, though that law is not perfect, nor is the East Rural Area fully protected.

“The Seminole County rural boundary is still in imminent danger,” Katrina Shadix, executive director of Bear Warriors United, said.

While the rural boundary and the East Rural Area it protects has been upheld multiple times, it would currently only take a 3-2 county commission vote to reduce the space.

“I think it makes it more powerful when the voters put it in place because that is the will of the voters,” Seminole County Commissioner Jay Zembower said. “Every time, at least since I’ve been involved as an elected official, when somebody said, ‘well, the rural boundary can be changed by the commissioners with a 3-2 vote,’ my answer is: ‘Well, it was the will of the voters to put it in place, and I’m not going against the will of the voters. It’s that simple.’”

But that doesn’t mean a commission never would. And that is why the county is giving voters the choice to make the protections stronger.

In its April 25 charter review, Seminole County’s Charter Review Commission approved a resolution that, following upcoming public hearings, would add a referendum on the Nov. 5 ballot that would allow voters to require a higher supermajority vote for any changes or transfers of land designated as “natural lands,” or to remove property from the county’s designated “rural area.” If approved, it would go into effect on Jan. 1, 2025. It had its first public hearing on May 2, where ballot language was added, and is scheduled to have its next public hearings on May 16 and June 6.

“The one thing that can help save the rural boundary and our natural lands in Seminole County is that these ballot initiatives make it to the amendments for the charter,” Shadix said. “Then we are golden. We're going to have that extra layer of protection, and it's going to require a supermajority vote, four out of five, that if they want to remove any land from the natural land program or Seminole Forever, it requires four out of five votes, not just three-to-two.”

This added protection can mean a lot for the future of the land.

“Protection means that you won’t see any subdivisions in the eastern part of the county,” Seminole County Commissioner Bob Dallari said.

“Our citizens are very engaged here. They’re very astute of what’s going on,” Dallari said. “They understand the importance of protecting not just the environment, but their neighborhoods. And if you want to be successful in this county, you have to listen to the community and the residents.”

And many see it as the gold standard of conservation in Florida.

“It is a very excellent example of farsighted individuals 40 years ago who could see the future, which was Orlando would eventually go coast to coast, and they wanted to put down a marker and say, ‘this area, we want to remain rural,’” Lesley Blackner, an attorney for environmental and wildlife organization Bear Warriors United, said.

Inside of the rural boundary, most tracts are limited to one home on every 5 or 10 acres of land. Any potential development beyond the rural boundary would be expensive because infrastructure such as roads, sidewalks, lighting, water and sewer would need to be added.

“There is really not a lot left to develop within Seminole County,” Seminole County Commissioner Jay Zembower said. “Between what the county owns and what the state owns within the county, I mean, we’ve got tens of thousands of acres of land that’s put aside. … There’s nothing really in play [that is not already part of the Corridor or the rural boundary].”

The extra protections are important because, while Zembower does not see changes to the rural boundary anytime soon, even if the referendum does not pass, no one knows what the future holds.

“Fifty, 60, 70, 80, 100 years from now, we’re not going to be here to know what’s going on,” he said. “There may be a need for the boundary to move an eighth of a mile one way or the other for whatever reason for infrastructure of public safety, or there may need to be, 200 years from now, some ability to grow the population or accommodate the population.”

Protecting the Corridor

The Florida Wildlife Corridor Act was passed by the state Legislature in 2021 and, in doing so, a total of $400 million was allocated to “encourage and promote investments in areas that protect and enhance” the Corridor, according to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

The Florida Wildlife Corridor is a network of close to 18 million connected acres — 10 million of which are protected conservation lands — throughout the state, winding from the northwestern edge of the panhandle to the southern tip of the Everglades, and includes significant areas of Central Florida, and Seminole County specifically.

While the money was allocated, there are concerns that it doesn’t do enough to save at-risk land.

“It’s not a self-executing statute,” Blackner said. “It says these lands are very important for maintaining biodiversity in the state of Florida, and every effort should be made to protect these lands. But it’s nothing to stop developers from still developing them, or to stop local governments from rezoning agricultural properties or authorizing development in the Corridor.”

A recent example of this is happening in the Split Oak Forest in Orange and Osceola counties. The 1,700-acre area inside the Corridor is home a gopher tortoise population that nearly 400 other animal species rely on for survival.

But on May 1, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission officials approved a proposal by the Central Florida Expressway Authority for a toll road to be built through some of Split Oak. This would remove conservation easements from 60 areas in exchange for a mitigation package of 1,550 acres — much of which are not similar to the original acreage — and millions of dollars for restoration and management.

“The Corridor is an idea, it’s a plan, it’s a vision, but it may not happen,” she said. “In reality, in Florida, everything can get built. … There’s no mechanism for making sure that the development doesn’t happen.”

The Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation, founded in 2010 by Tom Hoctor, Director of the Center for Landscape and Conservation Planning at the University of Florida, and conservation photographer Carlton Ward Jr., serves to play a role in helping determine which lands are key to protect and keep in conservation and collaborates with officials who work on acquisition.

The state does have programs in place to acquire land for conservation purposes, such as Florida Forever. While the Corridor Act doesn’t have its own regulatory teeth, the Florida Forever program, which has purchased nearly 1 million acres of land for about $3.3 billion since its inception in 2001, utilizes the funds from the statute to keep the lands in conservation and away from further development.

What land to purchase comes down to landowners and others applying for the program, and lawmakers deciding based on a self-made priority list. Willing sellers, cost and the potential environmental impact are among the top factors for priority setting.

With millions of acres still able to be developed, trying to decide which to purchase can be a daunting task, one that the Corridor is attempting to help solve.

“There’s 8 million acres of opportunity area,” Jason Lauritsen, chief conservation officer for the Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation, said. “They really fall into two categories: They’re either hubs or connections.”

Conservation hubs are described by the Foundation as “high-quality priority ecological areas,” including a rich array of species, native habitat and an intact water system. These are often what land acquisition programs such as Florida Forever target, and in many instances are incorporated as parts of state parks or forests.

Connections, however, are much more nuanced, often less of a priority to protect, but just as vital to the Corridor as a whole, Lauritsen said. As the name suggests, they provide critical connection points between conservation hubs.

“It’s the hallway connecting the rooms in which you live,” he said. “Those are the pieces that often are the most at-risk for a couple of reasons: One, often they’re degraded because they’re right next to development anyway. … And two, because they’re degraded, they don’t look that important, so they’re easier to sort of justify or write off or compromise because they don’t appear to be as pristine or as important.

“So they’re often in these areas that are already somewhat compromised, and they get gobbled up,” he said. “It’s not necessarily because people are trying to get away with anything, it’s just they don’t recognize the function of those connections.”

An informed public

A major reason connections are not recognized is that those outside of the conservation and governmental worlds just don’t know that the Corridor exists.

“I think public education is critical,” Julie Morris, executive director of the Florida Conservation Group, said. “The public has the power. This is a democracy. We vote, we decide who our leadership is going to be, so it’s incumbent on all of us in the conservation community to educate the general public because those are the folks that vote and decide our leadership. And it’s important for them to let their leadership know that land conservation is important.”

Lauritsen agrees that more education is paramount to the survival of a connected Corridor.

“The solution in my mind is to provide the tools and education and understanding for local folks to recognize where there are values and to help them make good decisions that they can be proud of,” he said. “I think most folks, in their heart of hearts, would do the right thing if they were educated on what that could be.”

Local work

While the future cannot be predicted, not everyone agrees that Seminole County’s rural boundary will be protected even in the near future without a fight, like the possible major change to the county’s charter.

Conservationists do agree on the importance and power of local voters for protections like the potential supermajority for changes to the rural boundary.

“Locals have to step up and try to incorporate the Corridor into their local land-use plans,” Blackner said. “The rural boundary … is incorporated into [Seminole County’s] charter.”

The Corridor, however, is not a regular talking point among Floridians, and not voted into existence like Seminole County’s rural boundary. Educating the public of its existence and its significance could change the outcome of the race for protection, however.

“I think education on a local level is critical, because people care about what’s right around them,” Morris said.

But how is that done? How can millions of Floridians learn about these millions of critical acres that traverse the entire state?

At the local level, officials are trying to incorporate the Corridor into printed materials, as well as developing programs to highlight the availability of putting land into conservation. And doing so has led to community involvement.

Through work between the landowners, conservationists and state and county officials, the Yarbrough Ranch acquisition by Florida Forever gave Seminole County key conservation acreage.

“We’re in a unique spot, with the state now taking down the Yarborough tract of land that fills in that portion of the Wildlife Corridor and ultimately starts to fully connect South Florida up through Osceola County, through Orange [County], up through Seminole, all the way up to Flagler County,” Zembower said. “The benefit is to the citizenry. Future generations will be able to see that wildlife that you otherwise would never see unless you went to a zoo or you traveled maybe down to the Everglades.”

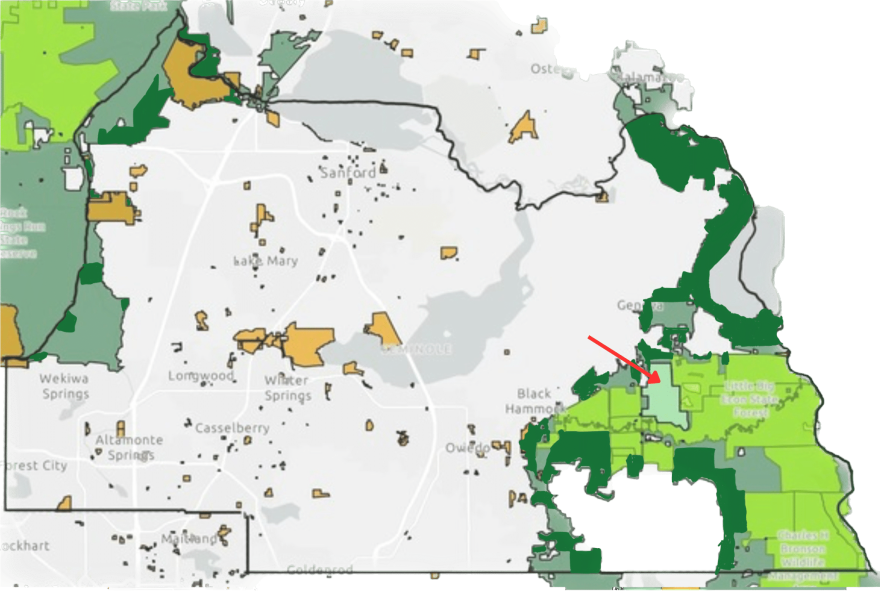

Our partners at the Oviedo Community News produced this interactive map illuminating the Wildlife Corridor’s various levels of protection.

Seminole County commissioners approved the Seminole Forever program ordinance in August 2023 and approved the new members of its acquisitions and restoration committee in November. Seminole Forever will attempt to mimic the larger, state-wide land-acquisition program Florida Forever.

“The education piece is really important, both from an awareness of the program being out there [purpose] and as an opportunity for folks,” Seminole County Leisure Services Director Rick Durr said. “Since … the passing of the Seminole Forever program, there’s not been a shortage of folks reaching out to our department, for example, almost on a weekly basis asking how they might be able to engage with the county.”

While the county has not conducted any formal outreach effort itself, as the program is in its infancy, Durr said that various individuals have requested to have their land be considered for acquisition through the Seminole Forever program. The county’s Acquisition and Restoration Committee, which will assist in land acquisition, has not yet determined its criteria for property evaluation but, once it does, it will provide its recommendations to the Board of County Commissioners and begin its formal outreach program, Durr said.

The Yarborough property had entitlements — approvals for landowners or developers to build on a property — on it prior to the rural boundary being created, which always put it at risk of being densely developed.

This is a similar scenario to other properties around the state, where “you have landowners that, arguably, many of them are farm or grove owners … that may be on their third, fourth, fifth generation of putting their blood, sweat and tears into this land [and] they’re looking for a buyout,” Zembower said, which makes it difficult to put them into conservation.

More education about the importance of the Corridor could help land-acquisition programs progress further and quicker in discussions with landowners before property is sold to developers, he said.

“If a property already has entitlements, they legally cannot [be taken] away,” Zembower said. “So they have to sit down at the table with those property owners and either negotiate a deal to buy it out or convince the state or federal government to put dollars in to buy it out.”

Despite Zembower being a Seminole County official, he sees the best opportunity for the state to protect the most land possible elsewhere.

“The best bang for the dollar is — if I was advising the state — is to try to get as much of that Wildlife Corridor you can in the panhandle region, because you can buy much more of it for the same dollars that you would buy a tract like Yarborough,” he said.

The Yarborough acquisition closed off a key part of the Corridor to development, and having the visualization of the Corridor available was a big reason why.

It even helped overcome the existing entitlements on the property.

“It’s not just a talking point anymore; it’s a piece on a map that we can say, ‘here’s a statewide map that was created that really established and helped establish a priority acquisition area that we were able to then use that designation as a positive toward our application,” Durr said. “It helped us tremendously in our application to the state.”

In Lake County, Jane Hepting, Lake County Conservation Council president, and her organization host large-scale events, with dozens of exhibits that attract hundreds of people, to help educate the public.

“We were asking people there things like, ‘what can government do? What can green business do? What can individuals do to protect our natural resources?’” she said.

But holding off development is a difficult proposition, as land owners have rights to sell to the buyers of their choice. Expos and printed material may not be enough.

“The game here isn’t trying to stop and halt all development, in part because that’s not realistic,” Lauritsen said. “Rather than rush to try to figure out where everything needs to be statewide, the solution, in my mind, is to provide the tools and education and understanding for local folks to recognize where there are values, and to help them make good decisions that they can be proud of.”