The general concept of reusing water is nothing new in Florida. But what is new, as of this year, are state rules allowing for utilities to treat and distribute recycled water for drinking.

RELATED: Drinking recycled water? In Central Florida, the day will come

Recycled water, also known as reclaimed water, is wastewater that is treated and recycled for another purpose. Right now, most reclaimed water in Florida is used to irrigate areas used by members of the public, like residences, golf courses, parks and schools.

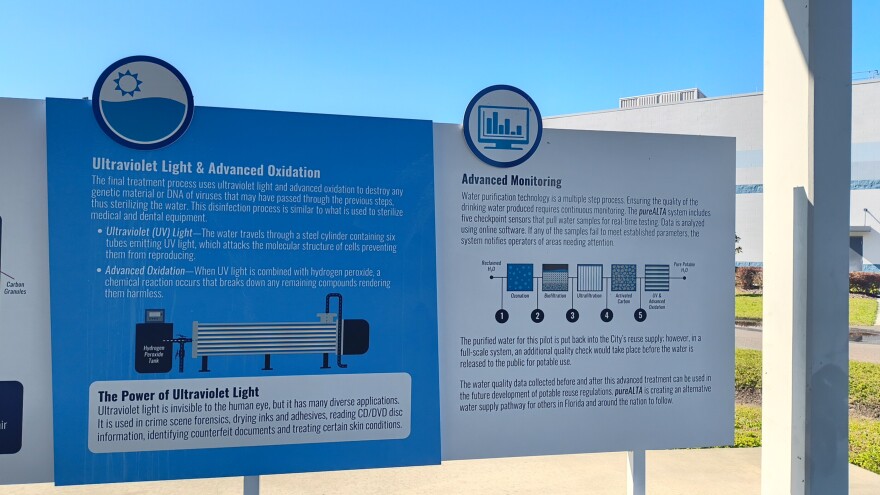

So far, no Florida utilities are treating and distributing reclaimed water to customers at scale. But some pilot projects in the state are successfully treating recycled water to drinking water standards. One of those projects is pureALTA, a state-funded pilot facility in Altamonte Springs.

“They’ve asked us to figure out how to do it, and we have figured out how to do it,” said City Manager Frank Martz. “It is chemically clean. It is biologically clean.”

Still, Martz and other officials know from experience that, at least initially, it can be challenging for people to accept the idea of drinking what used to be wastewater.

“The technology is proven. They’re allowing, kind of, the population to get used to the ideas of alternative water,” Martz said.

That gradual, ease-in approach tends to be a good strategy for helping people adjust, according to University of Pennsylvania Professor Emeritus of Psychology Paul Rozin. Much of Rozin’s research is focused on the psychology of contamination and disgust.

“It's a gradual persuasion, a gradual procedure,” Rozin said. “People get used to almost everything …. It’s just a matter of exposure. And necessity helps.”

That’s been the case in Singapore, Rozin said. In that country, at some water treatment plants, recycled water called “NEWater” is treated and delivered to customers for drinking, according to the national water agency. It began with a public launch event in 2002, where 60,000 people toasted Singapore’s birthday using bottles of NEWater.

But psychologically, an initial apprehension about drinking recycled wastewater makes sense, Rozin said. Human beings have evolved to try and avoid things that can cause disease.

“A lot of this is related to pathogen avoidance. Feces is a vehicle for pathogens,” Rozin said. “Everybody is opposed to feces.” That aversion to feces is universal across cultures, in everyone over the age of five.

There is some level of variation. “People vary enormously in how sensitive they are to disgust,” Rozin said.

But another key factor is something Rozin has described as “once in contact, always in contact.” It’s a feeling people experience: that once something perceived as “gross” comes into contact with another substance, that substance is forever contaminated — even if, scientifically, that isn’t the case.

“That's permanence, which is to say, that juice that you dropped the cockroach in will not be drunk a year later, if people remember what happened to it,” Rozin said. “We call it magical contagion, because it doesn't follow the principles of physics and biology.”

Still, it is possible to overcome disgust, Rozin said. “We all do things that are disgusting, that we get used to. And then we’re not disgusted anymore.”