Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissioners voted unanimously Wednesday in favor of rules for a regulated bear hunt, beginning later this year with a 23-day hunting season in December.

RELATED: Final vote approaches for a regulated bear hunt in Florida

Moving forward after 2025, bear hunting season dates will fluctuate annually based on population numbers and management objectives, but will be confined to Oct. 1-Dec. 31, according to the agency. Across Florida, FWC has seven Bear Management Units or BMUs, and the new rules establish Bear Hunting Zones within four of them.

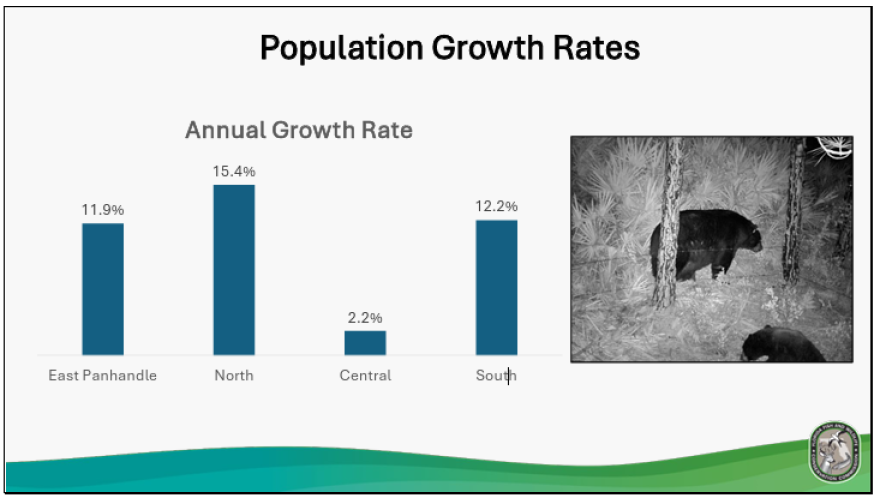

Within those four BMUs, there are three in which FWC estimates bear populations will grow by more than 10% annually. But that estimated growth rate is much lower in the Central BMU, which includes 13 counties in East Central Florida and the Ocala National Forest. There, bear population growth is estimated at 2.2%.

“The lower annual growth rate for the Central BMU subpopulation is due to lower adult female and cub survival rates, primarily because of vehicle collisions,” according to FWC. Statewide, vehicle collisions are responsible for 90% of all known bear deaths.

Hunting bears under the new rules will require permits, to be awarded by random drawing via FWC’s special opportunity permitting process, FWC Chief Conservation Officer George Warthen said Wednesday. Awarded permits will cost $100 for Florida residents and $300 for non-residents.

Applying for a permit will cost $5, with no limits on how many times a person can apply, but only one “bear harvest permit” will be awarded per person. But there’s an exception to that, in a new “private lands bear harvest program” established by the new rules.

The private lands program is meant to incentivize landowners with 5,000 or more acres of contiguous land to conserve bear habitat. Landowners accepted to that special program could be permitted to hunt and harvest 1-3 bears on their property, Warthen said Wednesday.

Permit quotas will be “data-driven” and adaptable, depending on bear population estimates for each respective BMU, according to FWC. The agency’s current plans call for capping this year’s quota at 187 permits, statewide. The fewest permits will be allocated to the Central BMU, whose quota is just 18 permits.

But those permit quotas will change annually, based on population trends and “hunter success rates,” Warthen said.

RELATED: Florida bear hunt lottery, limited permits part of proposed plan

“Commissioners, we're not asking you to establish a quota every year,” Warthen said. “Our staff are proposing that the hunting permit quotas would be established annually by the executive director or their designee, as informed by staff.”

Speaking during a public comment period Wednesday, Rachael Curran with the Jacobs Public Interest Law Clinic for Democracy and the Environment raised legal concerns about that strategy for determining quotas.

“I'm deeply concerned about the lack of due process afforded in this new rule,” Curran said. She said current rules call for FWC commissioners to decide on permit quotas: “It requires approval of the quota year after year.”

But the new rule “totally punts that to your executive director, really eliminating the public process,” Curran said.

Before voting Wednesday, FWC commissioners heard hours of testimony from more than 150 people who spoke for and against the bear hunt, or “harvest,” a term used by the state.

Many speaking in favor of the hunt spoke of the need to protect their cattle and other livestock, and raised safety concerns triggered by more cases of bear sightings.

“Families want to feel safe in their own yards,” said Gulf County Commission Chair Sandy Quinn. “Bears belong in their natural habitat, and encounters should be the exception, not the norm.”

Others described bear hunting seasons as a humane, proactive approach to managing bear populations.

“Our goal is to see Florida black bears thrive, and we are confident that establishing a designated bear hunting season will provide more advantages to this species than not having one,” said Elizabeth Bland, president of the American Daughters of Conservation’s Florida chapter.

But many opponents of the bear hunt said Florida’s bear problem is really an overdevelopment problem, due to much of the animal’s natural habitat getting cleared throughout the state.

“We've spent several hundreds of thousands [of dollars] filing lawsuits to stop development which would have destroyed bear habitat,” said Katrina Shadix, executive director of Bear Warriors United, a nonprofit which has said it’s suing FWC over the new rules.

Not all hunters in Florida want bear hunting seasons, Lauren Jorgensen told FWC commissioners Wednesday. Jorgensen’s family has been in the state for four generations and she and her husband have a cattle ranch in Suwannee County, she said.

“We have a lot of friends who are hunters, landowners. I'm here to let you know that not all the hunters support this hunt,” Jorgensen said. “We'd like to see nature in balance. We are conservationists.”

Since 2006, excluding vehicle strikes, there have been 42 documented incidents of physical contact between a person and a black bear in Florida, according to FWC data. Most have taken place in Seminole County, with nine incidents documented since 2006.

Twenty-eight of all physical human-bear incidents statewide involved a dog, according to FWC. The new rules approved Wednesday reintroduce the use of dogs in bear hunting, something that hasn’t happened in Florida since 1994. The change will take place over a delayed, two-year training process, Warthen said.

Some speaking Wednesday against the regulated bear hunt raised concerns about FWC’s bear population abundance estimates, arguing they aren’t a proper reflection of how bears are currently faring across the state. The agency’s most recent, valid population estimates are from 2015.

In response to those concerns, FWC staff said the agency’s population estimates form just one piece of their analysis, not all of it. The agency also uses multi-year tagging studies to model bear survival and reproductive rates.

“If we just had that old 2015 population number without the growth rate information, I would say we should be a little cautious,” said Gil McRae, director of FWC’s Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. “But having both [estimates and models] makes me more confident.”

Still, opponents insist the agency’s approach to a regulated bear hunt is shortsighted, lacking proper data and analysis.

“I cannot give a course in statistics in 30 seconds, but in the Central [BMU], the bear population may actually be declining without a harvest,” said Kimberly Buchheit, referencing that area’s 2.2% annual growth rate estimate. “I ask that the Central [hunting] zone be removed from consideration.”

The last time Florida held a regulated bear hunt was in 2015, when 304 bears statewide were “harvested” in two days. Reopening regulated bear hunting now will “provide access to the resource” while helping manage the population, Warthen with FWC told commissioners.

“For all game species, including bears, setting harvest limits that maintain populations is a well-understood science,” Warthen said. “This is reflected across North America, where almost all jurisdictions with resident black bear populations have regulated bear hunting seasons, and their populations are stable or increasing.”

Of the six states that don’t hunt bears — a group that up until Wednesday included Florida — the Sunshine State is home to the most bears, at more than 4,000, Warthen said.

Two of FWC’s seven commissioners were absent from the agency’s meeting Wednesday, the first of two days of meetings scheduled in Havana. All commissioners who were present Wednesday voted in favor of the bear hunt rules.

The vote of approval, held just before the lunch hour, was met with shouts and “boo’s” from people in the crowded room. FWC Chair Rodney Barreto chuckled: “Anybody surprised?”