Updated at 8:53 p.m. ET

Prosecutors in Paul Manafort's bank and tax fraud trial did not rest their case on Friday as had been expected earlier.

Instead, they called a witness to the stand who highlighted the sometimes murky line for Manafort between the personal and the political, and they said they expected to call one or two more witnesses on Monday before resting then.

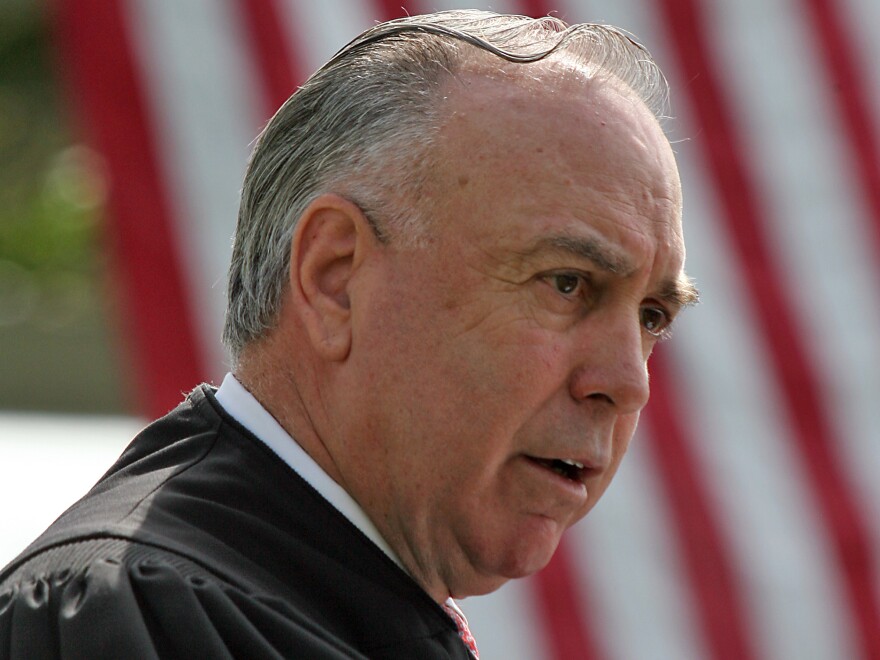

The ninth day of Manafort's fraud trial began with an unexplained five-hour delay. During much of that time, Judge T.S. Ellis III was in conferences with prosecutors and the defense.

White noise is played in the courtroom during such conferences so the public and reporters cannot hear what was being said.

Some 90 minutes after the expected start to the day's testimony, the judge briefly called in the jury. Ellis issued a warning reminding jurors to keep an open mind and not discuss the case with anyone, including each other. He then announced a break for an early lunch.

The banker's evidence

After another 45 minute delay to kick off the afternoon, Dennis Raico, a former vice president of Federal Savings Bank, finally took the witness stand for the prosecution.

Raico talked about the unusual and winding process that Manafort used in qualifying for two loans from the bank in 2016 and early 2017. Manafort ultimately borrowed $16 million. Raico discussed the role the bank's CEO, Steve Calk, played in that process.

Manafort met with several of the bank's executives, including Calk, for dinner in Manhattan in May of 2016. Calk wanted to meet Manafort, Raico said, after hearing he was involved in politics. Raico testified that Calk said that he'd be interested in serving in a Trump administration.

Raico said that a few days after Trump was elected, Calk called him to say he hadn't spoken with Manafort in a few days. Calk asked Raico to speak with Manafort to see whether Calk was up for nomination to become secretary of the Treasury or secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the incoming Trump administration.

Jurors already have heard testimony that Manafort reached out to the Trump transition team to discuss choosing Calk for secretary of the Army. Ultimately, Army Secretary Mark Esper was nominated and confirmed for that position.

Raico also testified on Friday that in the fall of 2016, a loan-approval committee Calk led signed off on Manafort's loan within a day. The committee did so, Raico said, even though there were questions about significant discrepancies between the income figure on his tax return and the figure in other financial documents.

"A plus B didn't equal C all the time," Raico said. He also said the political nature of Calk's involvement in the loans made him "very uncomfortable."

Andrew Chojnowski, also of Federal Savings Bank, was the final witness of the day on Friday. He testified that Manafort had signed loan papers confirming that he understood that it's illegal to make false statements during the applications process.

Speed bump

As recently as Thursday, prosecutors had said they expected to rest their case on Friday after two weeks of detailed testimony from accountants, bookkeepers, luxury vendors and Manafort's former business partner.

That timeline has now shifted.

Now prosecutors are expected to rest Monday, sometime after court resumes at 1 p.m. ET. They've spent the past two weeks working to illustrate how they say Manafort evaded taxes on millions of dollars by hiding money in shell companies and bank accounts based mainly in Cyprus.

They also allege that when Manafort's income dried up — after his most important political consulting client in Ukraine was ousted from power — Manafort lied to banks to qualify for loans to sustain his luxurious lifestyle.

Once prosecutors rest their case, the defense will have an opportunity to call witnesses to the stand. It's unclear whether Manafort's team will have any witnesses testify, but the trial still seems on track to conclude next week.

Manafort has pleaded not guilty and his defense attorneys have blamed any financial wrongdoing in the case on his former partner Rick Gates, who has pleaded guilty to related charges as part of an agreement with the Justice Department.

Prosecutors present a paper trail

Rick Gates may have been the prosecution's most exciting witness — as well as the centerpiece of Manafort's defense — but he was only one of many who have appeared in the trial.

Gates testified early in the week for parts of three days, but the rest of the trial has been consumed on both ends of his testimony by accountants and bankers who worked on Manafort's taxes and processed his bank loan applications, as well as vendors who sold him numerous high-priced items like luxury cars and custom suits.

Throughout the trial, prosecutors also have relied on emails sent to and from Manafort about his properties, as well as the accountants who worked with his finances.

That may have been a countermeasure against one of the defense's arguments, which was that Manafort was not intimately enough involved in his own finances to have deliberately committed financial crimes.

On Friday, the jury was shown an email Manafort sent Calk regarding the loan he was seeking, saying "I look to your cleverness in how to manage the underwriting."

Prosecutors must prove to jurors that if Manafort did evade taxes or misguide banks, he did so intentionally and not by mistake.

The New York property

To that end, prosecutors on Thursday questioned Melinda James, a loan assistant at Citizens Bank, and Peggy Miceli, a vice president at Citzens Bank.

Manafort received a $3.4 million refinancing loan from Citizens Bank in 2016 on a property he owned in New York. Prosecutors allege that in applying for that loan, Manafort lied by classifying it as his second home instead of an investment or rental property. Actually, they said, he was renting it out.

Miceli testified that Manafort would not have been eligible for a loan that large against the property had the bank known it was being rented. Earlier in the day, a representative from Airbnb testified that the property had been listed as available for rent for much of 2015 and 2016.

During James' testimony, prosecutors showed the jury an email from Manafort to his son-in-law notifying him that the bank was sending an appraiser to assess the property.

"Remember, he believes that you and Jessica are living there," Manafort wrote. Prosecutors said that showed Manafort knew he was misrepresenting how the home was being used.

The judge ... apologizes?

Ellis has had a massive effect on the quick pace of Manafort's trial, but he has had an even larger impact on the tone of the courtroom.

He has admonished prosecutors almost daily. Last week, he took them to task because he said they were sowing resentment in the jury over Manafort's wealth. The judge growled at them this week to "get to the heart of the matter."

On Thursday, however, Ellis offered something different: an apology — or close to it. And on Friday, prosecutors requested another one.

Ellis upbraided the government's lawyers on Wednesday for allowing an IRS expert witness into the courtroom to watch trial proceedings before he testified. But as prosecutors noted in a motion filed after court on Wednesday night, the judge had previously said the IRS witness could stay in the courtroom.

Prosecutors argued in the motion that Ellis' criticism on Wednesday could imply that the government was trying to skirt rules in its trial tactics and gain an unfair advantage, when in fact Ellis had explicitly given prosecutors permission for the expert witness to stay in the room.

"This prejudice should be cured," prosecutors wrote.

Ellis opened court on Thursday by admitting he "may have been wrong" and that he sometimes makes mistakes "like any human — and this robe doesn't make me any more than a human."

"Any criticism of counsel should be put aside," the judge said. "It doesn't have anything to do with this case."

He made statements during witness testimony Thursday related to bank fraud that again made prosecutors unhappy. While the government's lawyers were questioning a bank witness about a $5.5 million loan that Manafort applied for but didn't get, the judge said: "You might want to spend time on a loan that was granted."

Prosecutors filed a motion Friday arguing the judge's comment "misrepresents the law regarding bank fraud conspiracy, improperly conveys the Court's opinion of the facts, and is likely to confuse and mislead the jury."

Prosecutors asked the judge to provide a clarifying statement, but Ellis did not reference the motion in court on Friday. He did, however, share a lighthearted moment with prosecutor Greg Andres, a sometime antagonist inside the courtroom.

Andres admitted that he'd forgotten to submit something into evidence, and Ellis remarked that "confession is good for the soul."

"I think my soul's in a pretty good place," Andres piped back, as the jury laughed. "Or it should be after this process."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.