Deep inside the Port of Baltimore, past stacks of shipping containers and a plant that makes wallboard, sits the world's first, and only, nuclear-powered cruise ship – the NS Savannah.

The Savannah is the only nuclear-powered merchant ship the U.S. ever built, and the only nuclear vessel in the world designed with passengers in mind. As NPR's chief correspondent for all things atomic, I've wanted to see her for years.

So when the opportunity came up to take a tour recently, I climbed aboard.

Savannah's origin story began in the darkest days of the Cold War. In December of 1953, the very future of the world seemed to be in question. The Soviet Union had just detonated its first thermonuclear weapon. A year before, the United States had tested its own ten-megaton device on a remote Pacific island. The blast was so powerful, it wiped the island from the face of the Earth.

In a speech before the United Nations, then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower acknowledged the peril facing the world, but he refused to accept that the atom's only purpose was to vaporize mankind.

"The United States knows that peaceful power from atomic energy is no dream of the future," Eisenhower told the assembled diplomats. "The capability, already proved, is here today."

By the end of the decade, the U.S. Government had built the Savannah as part of a program known as "Atoms for Peace," which sought to demonstrate the good that nuclear energy could do.

The ship was launched in 1959, and its 74-megawatt nuclear reactor was powered up in 1961.

"Anybody could buy a ticket," says Erhard Koehler, the Senior Technical Advisor for the Savannah at the U.S. Department of Transportation's Maritime Administration, which owns the ship.

The ship was more of a proof-of-concept than an actual cruise ship. It could carry just 60 passengers, and it also had cargo holds for transporting goods.

Still, Koehler says, the ship was popular. "It was fully booked throughout its history." That history was brief – Savannah only carried passengers from 1962 to 1965.

Koehler says the decision to stop carrying passengers wasn't about safety. It was economic.

"If you stopped carrying passengers, you could reduce the number of stewards and reduce the cost of the program," he says.

The ship did see plenty of other visitors. Over its history, Savannah traveled to some 45 foreign ports in 26 countries. It's estimated that well over a million people boarded the ship to see its nuclear reactor at work. To facilitate the visitors, the Savannah sported an unusually large galley. "When it was in port, they would serve 500-700 people in a meal," Koehler says.

While the Savannah's nuclear reactor was revolutionary, the rest of the ship was actually unremarkable for the time it was built. "It wasn't very state-of-the-art," he says. "It's really a time capsule of what was the norm in the U.S. Merchant Marine in the 1950s and 60s."

Koehler takes me down to the reactor control room. It's located below, in the forward section of the ship.

It controlled a pressurized water reactor that used low-enriched uranium to produce heat. That heat was turned into steam that could run the ship's turbines, spinning the propeller and also producing electricity. The Savannah could cruise at 20 knots, which is similar to the speed of most cruise ships today.

We come down past the enormous turbines that once turned Savannah's propeller. The reactor control system is well lit. It's a small, one-of-a-kind system that allowed the ship's engineers to manage the reactor's power output as it plied the seas. Notably, the control room lacks any chairs: "By and large engineers in the 60s stood their watch; they didn't sit," Koehler says.

The operators could also command an emergency shut-down, or scram, of the reactor core. Scrams were rare aboard the Savannah, but one did take place in 1964, when the ship passed through a hurricane. A backup auxiliary motor run off of diesel power kept the ship going while engineers restarted the reactor.

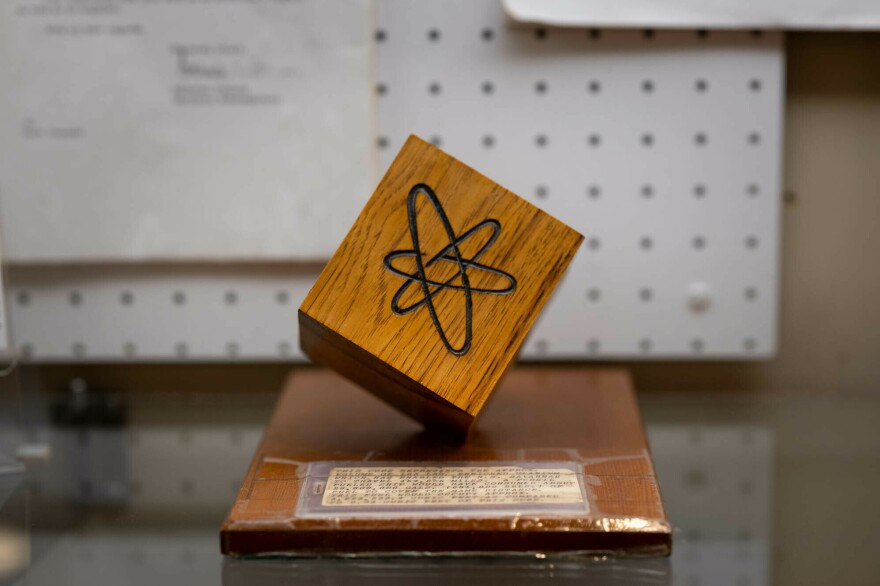

Back in the ship's main lobby, Koehler shows me a small wooden cube. It represents the volume of uranium fuel needed to let the Savannah travel 454,000 nautical miles– enough to circumnavigate the world well over a dozen times. Traveling the same distance with conventional fuel would have required approximately 28 million gallons of it.

But despite its dazzling efficiency, Savannah was never economically viable. It required special fuel-handling facilities to load and unload its nuclear core. And decommissioning the ship has taken decades and cost far more than it could have ever made moving cargo or people.

In the early 1970s, the Savannah's reactor was shut down and de-fueled. By that time, the ship had done what it was supposed to do – demonstrate a peaceful use of nuclear energy. "The program was ended, rather than continue to spend money for no real net effect," he says.

The NS Savannah has never sailed again. In the 80s and 90s it was berthed at the Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in South Carolina, before being put into storage. Decommissioning of the ship's nuclear components began in 2017.

In November of last year, its reactor was removed and taken to Utah for disposal. Koehler says full decommissioning of the ship's nuclear components will take another two years or so. At that point the Maritime Administration can dispose of the Savannah, Koehler says, but he hopes it will be protected.

"Our objective is not to scrap the ship," he says. "Our objective is to see the ship preserved somehow."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.